skip to main |

skip to sidebar

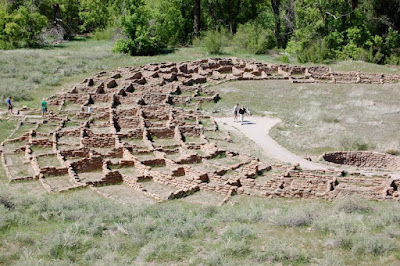

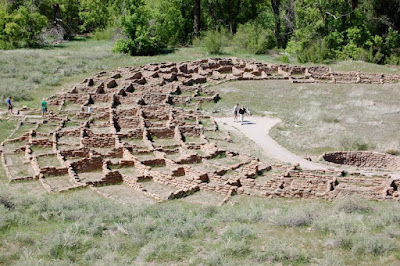

I vacationed this week in Santa Fe NM and one of its greatest assets is its 100+ art galleries. It is said to be the third largest art market in the country, after New York and LA. This time I was fortunate to be in a gallery when an artist whose work I had come to especially admire was paying a visit and we had a short conversation.

I vacationed this week in Santa Fe NM and one of its greatest assets is its 100+ art galleries. It is said to be the third largest art market in the country, after New York and LA. This time I was fortunate to be in a gallery when an artist whose work I had come to especially admire was paying a visit and we had a short conversation.

We don’t remember stories just because they happened (our poor brains would be overwhelmed). We only remember stories that give our lives meaning and identity. This is why taking away others’ stories is so devastating and why forgetting or losing our own stories leads to our feeling purposeless and directionless. Stories tell us where we have come from, what was important to our forbears, and gives us a compass to find new direction.

We don’t remember stories just because they happened (our poor brains would be overwhelmed). We only remember stories that give our lives meaning and identity. This is why taking away others’ stories is so devastating and why forgetting or losing our own stories leads to our feeling purposeless and directionless. Stories tell us where we have come from, what was important to our forbears, and gives us a compass to find new direction.

Martin Wolf is the star economics writer for the UK’s Financial Times. Today on her blog Naked Capitalism, Yves Smith dissects Wolf's latest column about the conflicting interests of the world’s two greatest exporting countries, China and Germany (or "Chermany" as he dubs them), and just about everybody else. Wolf says these two otherwise very different nations are in agreement that the world needs to keep buying their products but should stop borrowing so much. This message, says Wolf, is “incoherent” and pursuing such a strategy is a sure fire formula for deflation, the bogeyman of the Great Depression.

Martin Wolf is the star economics writer for the UK’s Financial Times. Today on her blog Naked Capitalism, Yves Smith dissects Wolf's latest column about the conflicting interests of the world’s two greatest exporting countries, China and Germany (or "Chermany" as he dubs them), and just about everybody else. Wolf says these two otherwise very different nations are in agreement that the world needs to keep buying their products but should stop borrowing so much. This message, says Wolf, is “incoherent” and pursuing such a strategy is a sure fire formula for deflation, the bogeyman of the Great Depression. What’s happening, according to Smith, is that all the participants in the global economic mess are each trying to resolve it on their own terms which, of course, can’t possibly work. An international problem needs an international solution but thus far there’s not much interest in that because politicians are listening only to their own constituents--a sure path to disaster. In Smith's words:

What’s happening, according to Smith, is that all the participants in the global economic mess are each trying to resolve it on their own terms which, of course, can’t possibly work. An international problem needs an international solution but thus far there’s not much interest in that because politicians are listening only to their own constituents--a sure path to disaster. In Smith's words:

It may be old news here but it isn't in continental Europe. The reports of clergy sex abuse in Catholic schools have rocked Germany and are spreading to other countries, as well. The wrinkle this time is that now the pope himself has been at least indirectly implicated in his previous capacity as archbishop.

It may be old news here but it isn't in continental Europe. The reports of clergy sex abuse in Catholic schools have rocked Germany and are spreading to other countries, as well. The wrinkle this time is that now the pope himself has been at least indirectly implicated in his previous capacity as archbishop.

Michael Lewis is one of the economics and finance journalists who are doing yeoman's work reporting the Great Recession and its origins. His piece "The End of Wall Street's Boom" was an early exposure of the insanity that had descended on New York's investment bank culture.

Michael Lewis is one of the economics and finance journalists who are doing yeoman's work reporting the Great Recession and its origins. His piece "The End of Wall Street's Boom" was an early exposure of the insanity that had descended on New York's investment bank culture.

In the previous post and elsewhere, I have written about the culture of Wall Street and its role in the 2008 economic debacle. Here is an amazing post by Yves Smith at her blog Naked Capitalism. It was originally a magazine article and is a LONG read but well worth the effort. The reader discussion that follows is also astonishingly excellent. Starting the post and in the comments you will find quotes from Reinhold Niebuhr, Hannah Arendt, George Orwell, and others to give you some idea of the level of conversation.

In the previous post and elsewhere, I have written about the culture of Wall Street and its role in the 2008 economic debacle. Here is an amazing post by Yves Smith at her blog Naked Capitalism. It was originally a magazine article and is a LONG read but well worth the effort. The reader discussion that follows is also astonishingly excellent. Starting the post and in the comments you will find quotes from Reinhold Niebuhr, Hannah Arendt, George Orwell, and others to give you some idea of the level of conversation.

Your old men shall dream dreams, and your young men shall see visions. (Joel 2:28)

A little after 8 am, five days a week 52 weeks a year, I get in my “In Box” an email newsletter from KurzweilAI.net. This is a web site created by inventor, author and futurologist Ray Kurzweil. (If you’ve ever used an electronic keyboard or voice-recognition software, you’ve probably made use of something he has a patent on.)

Kurzweil is a dreamer but, as his life has shown, he also has the ability to turn dreams into reality. Now in the latter part of his life (or maybe not “latter” if one of his dreams comes true) he is focusing most of his attention on creating dreams, big dreams—visions of the future both near and distant. Many of his futuristic visions have been dismissed by others as fantasy but not all. And given his past accomplishments many hesitate to dismiss anything he imagines as “impossible.”

Each of the little e-newsletters he sends out has about a half-dozen story summaries, with a link to click on to find the full story if it interests you. These stories are all about things happening right now in countless fields of research and technology. The topics include biology, medicine, nutrition, energy, computing, transportation, physics, astronomy, climatology, communication, robotics, and more.

Many of the stories are truly amazing but for me what’s most impressive is simply the sheer volume of the stories. They arrive day-after-day so that you can’t help but thinking, “Wow, there’s a lot going on in the world.” And the result of that is to make me really—hopeful.

That’s important because we live in what can be a very discouraging time. We can be discouraged by our own personal circumstance or by the economic gloom that has covered much of the developed world. I know it affects me. It’s obvious that—unlike the TV commercial—there is no Easy Button to get us out of the financial and economic mess we’ve gotten into. We’re going to be here for awhile.

Yet as this newsletter shows, around the world people are working to solve problems and make our lives better. Most of these people are working with little recognition—they fly below the media’s radar. Yet they are doing truly remarkable things, many of which someday (and in many cases it isn’t far off) are going to make this world of ours a better place to live.

In many ways Kurzweil provides little glimpses of humanity at its best, of human beings fulfilling what we imagine is our ideal function and purpose: helping each other to live better and happier lives. It brings to mind those early and simple instructions in the Bible: "till the garden and keep it" and “love your neighbor as yourself.”

Obviously, however, that isn’t all that’s going on in our world. Indeed, what makes these newsletter articles stand out is that they are often so unlike what is in the news much of the time. Yet one other hopeful thing is that we seem to be asking serious questions about why that is. We are wondering about the ways we are spending our time and talents, energy and resources. We are asking serious questions about our collective values and priorities.

The 2008 financial meltdown has caused a harsh spotlight to fall on Wall Street and for good reason. Certainly the causes of the Great Recession are varied and complex but the Wall Street investment “too big to fail” mega-banks must take a lot of the blame. Their ever more complicated, multi-trillion dollar financial schemes and products (financial weapons of mass destruction Warren Buffett has called them) collapsed like a house of cards, very nearly bankrupting the country and much of the rest of world. The reverberations and repercussions are not over yet nor, apparently, are many of the risky bank practices that got us into this mess.

The 2008 financial meltdown has caused a harsh spotlight to fall on Wall Street and for good reason. Certainly the causes of the Great Recession are varied and complex but the Wall Street investment “too big to fail” mega-banks must take a lot of the blame. Their ever more complicated, multi-trillion dollar financial schemes and products (financial weapons of mass destruction Warren Buffett has called them) collapsed like a house of cards, very nearly bankrupting the country and much of the rest of world. The reverberations and repercussions are not over yet nor, apparently, are many of the risky bank practices that got us into this mess. It has perhaps always been true that one of humanity’s greatest obstacles has been lack of imagination. We are creatures of habit. Those who ask “what’s over that hill?” or “what if we did it this way?” have more often been laughed at or scared off than listened to. What is remarkable about the world’s recent history is that such people have been given much more credibility and opportunity. Still, changing habits and ways of thinking are hard for all of us.

It has perhaps always been true that one of humanity’s greatest obstacles has been lack of imagination. We are creatures of habit. Those who ask “what’s over that hill?” or “what if we did it this way?” have more often been laughed at or scared off than listened to. What is remarkable about the world’s recent history is that such people have been given much more credibility and opportunity. Still, changing habits and ways of thinking are hard for all of us.

There has been a lot of speculation on whether the ELCA’s current financial woes are the result of the approval of gay clergy at last summer’s churchwide assembly. The other explanation, of course, is that it’s the result of the country experiencing the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression.

There has been a lot of speculation on whether the ELCA’s current financial woes are the result of the approval of gay clergy at last summer’s churchwide assembly. The other explanation, of course, is that it’s the result of the country experiencing the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression. I think he goes awry, however, when he concludes that this increase means “the picture may not be as bleak as the membership data alone indicates.” There is no reason to see an increase in “constituents” as a prelude to increased membership. Rather, it simply confirms the trend experienced by most churches that people’s relationships with churches are increasingly distant and temporary. Younger adults, especially, choose selectively among church activities and move in and out of church as they choose. The life-long church member is becoming a very rare breed.

I think he goes awry, however, when he concludes that this increase means “the picture may not be as bleak as the membership data alone indicates.” There is no reason to see an increase in “constituents” as a prelude to increased membership. Rather, it simply confirms the trend experienced by most churches that people’s relationships with churches are increasingly distant and temporary. Younger adults, especially, choose selectively among church activities and move in and out of church as they choose. The life-long church member is becoming a very rare breed.

One other statistic of interest was membership changes at the extremes of congregation size. “Churches with memberships of 100 and less reported a decline in membership of 2.25 percent, while churches with 3,000 and more members increased membership by 1.9 percent.” Small congregations have, until recently, been the backbone of mainline churches. One of the legacies of the Great Recession may be to permanently change that makeup. Not only are small congregations not competitive in a time of cafeteria Christianity, they are now financially unworkable, absent a large financial endowment. It seems almost certain that mainline denominations will increasingly be made up of fewer yet larger congregations.

Jeremy Warner is Assistant Editor of the UK’s Daily Telegraph and a highly regarded economics commentator. In his most recent column he looks down the tracks to see what’s coming and what he sees is not very reassuring. Basically the world’s economies are looking in the mirror and seeing—Greece.

Jeremy Warner is Assistant Editor of the UK’s Daily Telegraph and a highly regarded economics commentator. In his most recent column he looks down the tracks to see what’s coming and what he sees is not very reassuring. Basically the world’s economies are looking in the mirror and seeing—Greece. What Warner is saying is that no matter how central governments shuffle and deal their fiscal cards, serious economic adjustments are now unavoidable. Greece is the first country to painfully discover this but it will not be the last.

What Warner is saying is that no matter how central governments shuffle and deal their fiscal cards, serious economic adjustments are now unavoidable. Greece is the first country to painfully discover this but it will not be the last.

Via Mike Shedlock we learn of another example of the craziness of today’s financial world. The Nevada Federal Credit Union is paying its customers to withdraw their money. Yes, their message is: Please take your business elsewhere, we don’t want it. Why? Because it is costing them to hold money. They cannot find any worthwhile loan opportunities (it is Nevada, after all) and they can't engage in the high risk investing/gambling that the big boys on Wall Street can. They are paying more in required deposit insurance (.4%) than they can earn with short term Treasuries (.25%).

Here is a simple example of how artificial is the Fed’s current policy of holding interest rates at nearly zero--in other words, more smoke and mirrors. Economists and financial bloggers like Shedlock have been saying for a couple years now that most government interventions to right our economic ship are counterproductive. Their goal is to restart the country’s economic engine but do nothing to fix its problems. When your car needs a tune-up, if not an overhaul, pouring additives in the tank may get you a few more blocks or miles, but you’re still going to end up on the side of the road with the hood up.

Why do you spend your money for that which is not bread, and your labor for that which does not satisfy? (Isaiah 55, reading for the Third Sunday in Lent)

Since their development in the so-called Axial Age (mid-first millennium BCE), the world’s great religious traditions have all tried to deal with the place of material wants and comforts in human life. More specifically they have addressed the paradox that our pursuit of material prosperity and the happiness we assume it brings often doesn’t make us happy but only more miserable, at least in the long run.

Buddhism teaches that it is desire itself which is the source of human misery. Judaism doesn’t go that far but says that our first desire must be fellowship with God which then trumps all others. As part of that tradition, Christianity and Islam endorse this view. Our unhappiness then, as Isaiah says here, comes from “labor[ing] for that which does not satisfy.” In Jesus words (Matthew 6), “But strive first for the kingdom of God and his righteousness, and all these things will be given to you as well.”

In pietistic fashion, such admonitions as these are usually applied individually. We easily imagine a prophet or preacher wagging their fingers at us as our conscience joins in the accusation: Yes, I really am too greedy, too materialistic, too selfish, etc., etc. In fact, it is not at all clear that is the intent of this text from Isaiah. More to the point today, it is not at all clear that in the modern world that what you or I individually think or feel is what is really important. For even as modernity has championed the rights and freedoms of the individual, the complexity of modern life has meant that the most important choices and values are those determined collectively through our political and economic structures.

We are in the midst of the worst economic convulsion since the Great Depression eighty years ago. It has not resulted in the same depth of unemployment or business collapse but it is likely to persist for years to come. The problem, in the view of many economists, is that the recovery cannot take the form of a “bounce back” to what was before because what was before was unsustainable.

In fact, our economic problems have been decades in the making. This “Great Recession” is largely the result of previous attempts to cover over those problems rather than confront them directly. The fear is that we will make the same mistake again in trying to pull out of this downturn. It could happen, however, because there is no consensus on what the real solution ought to be.

In fact, our economic problems have been decades in the making. This “Great Recession” is largely the result of previous attempts to cover over those problems rather than confront them directly. The fear is that we will make the same mistake again in trying to pull out of this downturn. It could happen, however, because there is no consensus on what the real solution ought to be. In Olive Stone’s 1987 movie Wall Street, bankster poster boy Gordon Gekko declares unambiguously that “greed is good.” The events of the past few years have shown that is certainly the philosophy of Wall Street and of the international lords of finance. Over the past thirty years or so, it very nearly became the philosophy of American culture generally and of much of the developed—and developing—world.

In Olive Stone’s 1987 movie Wall Street, bankster poster boy Gordon Gekko declares unambiguously that “greed is good.” The events of the past few years have shown that is certainly the philosophy of Wall Street and of the international lords of finance. Over the past thirty years or so, it very nearly became the philosophy of American culture generally and of much of the developed—and developing—world. Most of our political and economic leaders know only this tune, however. It’s all they ever learned. And that’s probably true for most of us. Yet the signs are growing more numerous and more ominous that we, collectively, have to learn a new way of doing this thing we have called “the good life.”

Most of our political and economic leaders know only this tune, however. It’s all they ever learned. And that’s probably true for most of us. Yet the signs are growing more numerous and more ominous that we, collectively, have to learn a new way of doing this thing we have called “the good life.”

I vacationed this week in Santa Fe NM and one of its greatest assets is its 100+ art galleries. It is said to be the third largest art market in the country, after New York and LA. This time I was fortunate to be in a gallery when an artist whose work I had come to especially admire was paying a visit and we had a short conversation.

I vacationed this week in Santa Fe NM and one of its greatest assets is its 100+ art galleries. It is said to be the third largest art market in the country, after New York and LA. This time I was fortunate to be in a gallery when an artist whose work I had come to especially admire was paying a visit and we had a short conversation. We don’t remember stories just because they happened (our poor brains would be overwhelmed). We only remember stories that give our lives meaning and identity. This is why taking away others’ stories is so devastating and why forgetting or losing our own stories leads to our feeling purposeless and directionless. Stories tell us where we have come from, what was important to our forbears, and gives us a compass to find new direction.

We don’t remember stories just because they happened (our poor brains would be overwhelmed). We only remember stories that give our lives meaning and identity. This is why taking away others’ stories is so devastating and why forgetting or losing our own stories leads to our feeling purposeless and directionless. Stories tell us where we have come from, what was important to our forbears, and gives us a compass to find new direction.