I vacationed this week in Santa Fe NM and one of its greatest assets is its 100+ art galleries. It is said to be the third largest art market in the country, after New York and LA. This time I was fortunate to be in a gallery when an artist whose work I had come to especially admire was paying a visit and we had a short conversation.

I vacationed this week in Santa Fe NM and one of its greatest assets is its 100+ art galleries. It is said to be the third largest art market in the country, after New York and LA. This time I was fortunate to be in a gallery when an artist whose work I had come to especially admire was paying a visit and we had a short conversation.Richard Potter works in a technique called encaustic. Encaustic originated with ancient Greek ship builders who used heated wax to seal the hulls of their boats. Sometimes they added colored pigments to the wax for decoration and this eventually led to a new painting technique. Examples survive from the 2nd c. AD but its use goes back much earlier.

After languishing, the technique was rediscovered in the 20th c. and has become especially popular in the past twenty years. Today encaustic painting often includes collage. Layers of wax are used to hold almost anything to the board or canvas. Looking closely at Potter’s works you will see blades of grass, flower petals, string, paper and other items found around his rural studio location.

Looking at his newer works I also noticed small bits of printed text and music and I mentioned that to him. Potter laughed and said he’s always looking for ways to include Beethoven. He also named other composers and authors that he likes and then made an interesting observation. I include these things because we are losing our stories, he said—the myths, tales, and heroes which give culture its character and identity. On the gallery web site he says his painting “is a way of keeping our story alive, what I call the continuity of parables.”

Potter is one of many who are increasingly alarmed at our loss of common shared stories. This has been identified as one of the primary characteristics of postmodernism. It is one consequence of the mixing of peoples and cultures brought about by modern transportation and communication. Not only are new ideas, stories and traditions introduced when people move physically. Modern mass media does the same via television, movies, books, music, and the internet.

As just one recent example, rap music which originated in the American Black ghetto can now be found in poor urban areas on every continent. That rap has become a universal language for impoverished and oppressed young people around the globe may well be a good thing. It is obviously filling a need and may prove to have surprising power.

The question Potter and others are asking, however, is (to use his example) what happens to Beethoven? As our planet becomes increasingly homogenized, what happens to its individual cultural traditions, to their unique artists, prophets, heroes and thinkers, to the countless millions of stories which give each culture and its members their identity?

Recently samples of American high school seniors were shown to do poorly on the history and government test given to those applying for US citizenship. Other surveys have shown that most of those who identify themselves as conservative evangelicals or fundamentalists have very poor knowledge of the content of the Bible they claim to believe so seriously, often little better than the average public. I discovered early in my confirmation teaching career that most of my students couldn’t distinguish between Martin Luther and Martin Luther King. They both occupied in their minds some vague and shadowy entity called “the past.” Meanwhile the Texas State Board of Education has decided that Thomas Jefferson will now be viewed as only a bit player in the country’s founding because it disapproves of his deism and promotion of separation of church and state.

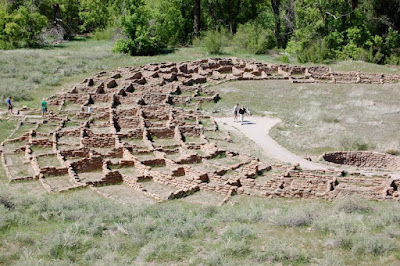

This week I also visited Bandelier National Monument. This national park includes the village ruins of Ancestral Pueblo People who inhabited this valley from roughly 1150-1550, abandoned before European colonists ever knew of its existence. Santa Fe itself is celebrating the 400th anniversary of its founding and establishment as capital of the province of New Spain in 1610, even while recognizing its earlier settlement by thousands of Pueblo People. Yet most of us know little or nothing of these stories, remembering only Jamestown (1607) and Plymouth Rock (1620) when thinking of America’s first settlers.

Conflicting stories and resulting confusion is nothing new. In the past, it was the “winners” who decided which stories would be remembered and which forgotten. Now we are more accepting of other cultures, past and present, but are uncertain what to do with all of them. Often we get lost in endless arguments about which stores are “true” or right when we feel the stories we cherish are somehow under threat, especially when political or religious competition intensifies.

This coming week in the church calendar, Holy Week, is all about stories. Again the modern question will arise: Are these stories “true”? It may well be, as many scholars now say, that few of the events described actually happened. In some ways this can hardly be a surprise given how different are each of the four gospel accounts of that week. But is that where the “truth” of these stories is even found?

We don’t remember stories just because they happened (our poor brains would be overwhelmed). We only remember stories that give our lives meaning and identity. This is why taking away others’ stories is so devastating and why forgetting or losing our own stories leads to our feeling purposeless and directionless. Stories tell us where we have come from, what was important to our forbears, and gives us a compass to find new direction.

We don’t remember stories just because they happened (our poor brains would be overwhelmed). We only remember stories that give our lives meaning and identity. This is why taking away others’ stories is so devastating and why forgetting or losing our own stories leads to our feeling purposeless and directionless. Stories tell us where we have come from, what was important to our forbears, and gives us a compass to find new direction.In this confusing time of intermixing cultures, we need to hang on to our history and traditions but do so with a looser grip. We can both celebrate our stories and at the same time recognize that they are not everyone’s stories, nor do they need to be. The stories of the world’s peoples are not in competition. We do not have to promote ours as true and everyone else’s as false. Indeed much of the tension in the world today is the result of people fearing their culture and values are being replaced by someone else’s. Their fear and anger are understandable.

We are entering a period of history unlike any other. Yet to go forward we must retain a connection with where we have come from. Our ultimate goal will be to achieve what Richard Potter calls a “continuity of parables.” Each nationality and culture will contribute their individual stories to a larger global tale, like the streams joining to make a great river. Leaving no one out, we will all add to this the most amazing of stories, that of human civilization itself.

No comments:

Post a Comment